COLORADO’S SECTION LINE ROADS

Sec. 3931 (Mills Ann. St., Chapter 108; Colorado Laws 1891) conferred upon county commissioners an interesting power over federal lands “in the public domain”.

“…Provided, the commissioners of the county may, at any regular meeting, by a order of the board, declare any section or township line on the public domain, a public highway; and on and after the date of such order, which shall be attested by the clerk, under seal of the county, and recorded in the office of recorder of deeds, the road so laid out shall be a public highway…”. 1

Roads laid out in accordance with Sec. 3931 had rights-of-way 60 ft. in width measured 30 ft on each side of the section line. (Sec. 2971, G.S. (1877)) The only section line on public lands officially recognized by the federal government was the line surveyed by the General Land Office. (GLO) (Land Ordinance of 1785; R.S. 2395 (1875); 43 U.S.C. 751) In the absence of a GLO survey there would not be interior section lines. This author has encountered two unsurveyed townships and there may be several more. For example, a large area south of Douglas Pass, lying in T6S, R102W and 103W has never been surveyed and lacks any interior section lines. (See: USGS, 7.5 Min Quad; Douglas Pass, CO (1964)) The validity of the section line road, then, depends upon whether there was or is today a federally recognized section line.

In compliance with Sec. 3931 many counties adopted resolutions declaring all section lines within their boundaries to be “public highways”. Many of the designated sections had yet to be settled under Homestead or land sale at the time of the enabling resolution. Still other sections had yet to be surveyed by the General Land Office (GLO). Section lines were, of course, arbitrary surface lines imposed by the “grid” pattern first established by the Ordinance of 1785 and its later counterpart R.S. 2395 (1875). Their designation as public highways under Sec. 3931 was illogical, if not outright absurd. What few roads existed in the latter 1800’s did not generally follow these arbitrarily drawn section lines. Transportation was by walking or on horseback or on bicycles. Roads paralleled surface watercourses to allow travelers and their stock to slake their thirsts. Actual road construction was performed by human or animal muscle and not by motor-powered machine. Thus, a road skirted around physical obstacles whenever possible rather than climbing over mountains, cliffs, buttes and mesas.

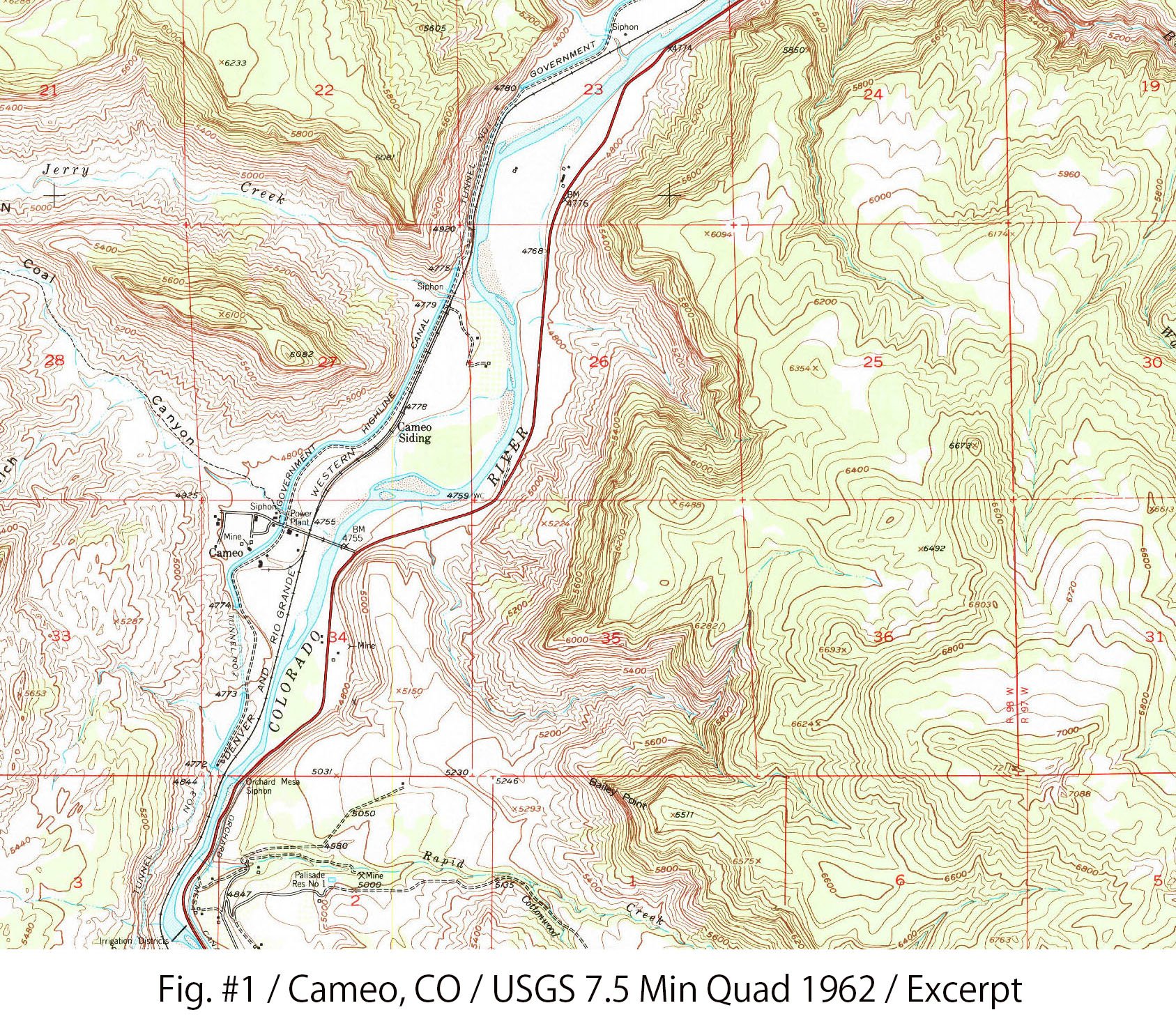

To illustrate the absurdity of “grid-like” section line roads compare Fig. #1 with Fig. #2 below. Both depict the same area. Fig. #1 shows the section lines while the photograph shows the terrain. Roads on the section line would, by necessity, climb vertical cliff walls! They bear no relation to the land route created by actual road construction or public travel.

Some section line roads did, in fact, become regularly traveled highways and, today, they handle heavy traffic volumes on a daily basis. But these may be the exception as there are more section lines in Western Slope counties than there are actual graded roads, whether paved or unpaved. These undeveloped section line roads have lain dormant for decades: neglected, forgotten and disregarded by county administrators. The early settlers, and today’s farmers, ignored them preferring, instead, to follow the natural terrain. With the intense urbanization of the Western Slope has come claims of public access across these dormant section line roads.

These claims, of course, are not based upon the rationality of the road’s location but simply upon the recordation of what can only be described as an outmoded resolution.

There is a three-tiered analysis to determine whether a section line road is valid. First, was the section line in the public domain when designated by the county commissioners? Second, did the federal government empower county commissioners to acquire easements across federal lands? Third, did the county comply with the specific federal authorization?

Available for Disposition / The Necessity of a GLO Survey: Both federal and state courts have defined “public land” or “public domain” as meaning all “…land as is open to sale or other disposition under general laws…” Bardon v. Northern Pac. R. Co. 145 U.S. 535, 538 (1892); Board of County Commissioners of Cheyenne County v. Ritchey 888 P.2d. 298, 300 (Colo. App. 1994) Land that is part of an Indian reservation is not part of the public domain. Ute Indian Tribe v. State of Utah 716 F.2d. 1298, 1305 (10 th Cir., 1983) Title to the public lands of the federal government is determined by federal law, not state law. Hughes v. State of Washington 389 U.S. 290, 292 (1967) quoting from Borax Consolidated, Ltd. v. City of Los Angeles 396 U.S. 10, 22 (1935).

Public land was not sold or allowed open for homesteading unless a GLO survey had first been performed setting the official boundaries for sections, townships and ranges. As emphatically stated in Public land was not sold or allowed open for homesteading unless a GLO survey had first been performed setting the official boundaries for sections, townships and ranges. As emphatically stated in Cox v. Hart 260 U.S. 427, 436 (1922): 260 U.S. 427, 436 (1922):

“Until all conditions as to filing in the proper land office and all requirements as to approval have been complied with, the (public) lands are to be regarded as unsurveyed and not subject to disposal as surveyed lands. (Citations Omitted)… In other words, to justify the application of the term ‘surveyed’ to a body of public land something is required beyond the completion of the field work and the consequent laying out of the boundaries, and that something is the filing of the plat and the approval of the work of the surveyor.”

(Emphasis Supplied)

Cox prescribes two essential dates: the date the survey was performed and the date when the GLO Surveyor General approved both the survey notes and the survey plat. Until this latter date the land was not eligible for disposition under the Land Sale Act of 1820 (April 24, 1820; 3 Stat. 566), the Homestead Act of 1862 (5.20.1862; Chapter LXXV), including its many variants or the Mining Act of 1872 (30 U.S.C. 29) and, therefore, was not “in the public domain”.

States Lack Authority Over Disposition of Interests in Federal Public Lands: Title to the public lands of the federal government is determined by federal law, not state law. Hughes v. State of Washington 389 U.S. 290, 292 (1967) quoting from Borax Consolidated, Ltd. v. City of Los Angeles 396 U.S. 10, 22 (1935). Title to private lands (i.e., post-patent) is determined by state law, even if the U.S. government is a party to the lawsuit. Oregon ex rel State Land Board v. Corvallis Sand & Gravel Company 97 S.Ct. 582, 587 (1977) (dealing with title to the bed of navigable rivers); U.S. v. O’Block 788 F.2d. 1433, 1435 (10 th Cr., 1986) In Hamilton v. Noble Energy 220 P.3d. 1010 (Colo. App. 2009) the court held that conveyances after patent issuance are governed by state law. (Id. at Pg. 1013) The court quoted from Packer v. Bird 137 U.S. 661, 669 (1891) (Once a U.S. patent is issued “whatever incidents or rights attach to the ownership of property conveyed by the government will be determined by the states”).

The interface between state and federal governments over public lands within the state’s boundaries raises the issue of Article IV, §3, cl. 2, U.S. Constitution. 2 The Property Clause, and its related Supremacy Clause, were applied in Kleppe v. New Mexico 426 U.S. 529 (1976). New Mexico legislated on protection of wild horse herds within public lands. The U.S. Forest Service had similar but its own ideas for such protection. In striking down the state action the Court said:

“Absent consent or cession a State undoubtedly retains jurisdiction over federal lands within its territory, but Congress equally surely retains the power to enact legislation respecting those lands pursuant to the Property Clause. … And when Congress so acts, the federal legislation necessarily overrides conflicting state laws under the Supremacy Clause.” 3

426 U.S. at Pg. 543

Quoting from Camfield v. United States 167 U.S. 518, 526 (1897), the Supreme Court held that “…a different rule would place the public domain of the United States completely at the mercy of state legislation…”. 426 U.S. at Pg. 543. The Kleppe court further held that the power over the public land thus entrusted to Congress is without limitation. 426 U.S. at 539. Resolution of any conflict is not based upon the existence of a conflict between the state and federal legislation. Florida Lime & Avocado Growers, Inc. v. Paul 373 U.S. 132, 142 (1963) (The test of whether both federal and state regulations may operation, or the state regulation must give way, is whether both regulations can be enforced without impairing the federal superintendence of the field, not whether they are aimed at similar or different objectives.”)

County governments do not have authority to decree the existence of easements over public lands. Any right to do so must rely upon specific federal, not state, statutes. The only such federal statute is R.S. 2477.

R.S. 2477 Did Not Authorize Roads “By Decree”: Between 1789 and 1866, the federal land policy was based upon “reservation”: i.e., the withholding of federal land from non- federal entities except for specified purposes. Obtaining an easement across federal land required a literal “Act of Congress”. An excellent discussion of this early policy is found in Western Aggregates, Inc. v. County of Yuba 130 Cal.Rptr. 436, 446 (Court of Appeal, 3rd District; 2002) Between 1866 and 1976, Congress changed that policy by enacting Sec. 8, 1866 Mining Act (39th Congress; Sess. I, Ch. 262-63; 43 U.S.C. 932; Repealed October 22, 1976) otherwise known as “R.S. 2477”. Under R.S. 2477 both private persons and state or county governments were granted self-actuating powers to construct public highways on unreserved federal land. Since 1976, the federal land policy has been set forth in the Federal Land Policy Management Act (FLPMA) (Public Law 94-579; 43 U.S.C. 1701-85). Under FLPMA private citizens and state and local governments may not obtain easements or create roads on federal lands except after qualifying for a land use permit. Both the application and the permit are strictly defined in regulations adopted by Interior’s Bureau of Land Management or Agriculture’s U.S. Forest Service. (Id.)

R.S. 2477 simply stated: “The right of way for the construction of highways over public lands, not reserved for public use, is hereby granted.” R.S. 2477 has long been interpreted as an open offer of dedication of federal lands for public highways, with state law being the determining law on “public highway”. Brown v. Jolley 387 P.2d. 278 (Colo. 1963); Gold Hill Development Company L.P. v. TSG Ski & Golf 378 P.3d. 816, 823 (Colo. App. 2015). There are only two requirements under R.S. 2477: (1) a physical route over land then in the public domain; and, (2) acceptance of the dedication in terms of the offer by either actual road construction or repetitive travel over the land route by the public. As set forth in Southern Utah Wilderness Alliance v. Bureau of Land Management 425, F.3d. 735, 741 (10th Cir., 2005) (SUWA)

“The establishment of R.S. 2477 rights of way required no administrative formalities; no entry, no application, no license, no patent, and no deed on the formal side; no formal act of public acceptance on the part of the state or localities in whom the right was vested.”

Colorado has long recognized a low level of public use – often called the “necessary or convenient” standard – as the measure of acceptance of the federal offer to dedicate public land for the construction of highways under R.S. 2477. As summarized in Brown v. Jolley 387 P.2d. 278, 281 (Colo. 1963).

“…(RS 2477) is an express dedication of a right of way for roads over unappropriated government lands, acceptance of which by the public results from ‘use by those for whom it was necessary or convenient.’ It is not required that ‘work’ shall be done on such a road, or that public authorities shall take action in the premises. User is the requisite element, and it may be by any who have occasion to travel over public lands, and if the use be by only one, still it suffices. ‘A road may be a highway though it reaches but one property owner.”

(Emphasis Supplied)

Brown was rendered in 1963 but was not the first case to use the lower standard. See: Sprague v. Stead 56 Colo. 538, 543, 139 P. 544, 546 (1914); Nicholas v. Grassler 83 Colo. 536, 537, 267 P. 196, 197 (1928); Leach v. Manhart 102 Colo. 129, 133, 77 P.2d. 652, 653 (1938) The lower standard was even applied in the U.S. District Court, Colorado. Wilkenson v. Department of Interior of U.S. 634 F.Supp. 1265, 1272 (D. Colo. 1986) In 2023, the 10th Circuit Court of Appeals disapproved the Brown doctrine. High Lonesome Ranch, LLC v. Bd. of Cty. Comms’rs, Garfield County 61 F.4th 1225 (10th CCA; 2023)

Brown contravenes congressional intent for the same reason we noted in San Juan County (754 F.3d. 787, 799 (2014). The acceptance standard is too lenient. In divining congressional intent, we have to turn to R.S. 2477’s phrase ‘for the construction of highways’. San Juan County, A public-use standard requiring only that the use be ‘as often as the public finds convenient or necessary’ departs from this R.S. 2477 phrase and thus from Congress’s intent in enacting that statute. ...

61 F.4th at Pg. 1245 (Emphasis Supplied)

R.S. 2477 was an offer to dedicate unreserved federal land in the public domain for public highways. The measure of acceptance of this offer was by one or the other of two methods. Actual construction of a road approved by the county commissioners definitely proved acceptance. An example is Mesa County Road V laid out in 1893 by Mesa County BOCC and built according to a commission approved contract. Pitkin County’s Rock Creek Wagon Road is another example of a constructed county road. Alternatively, county commissioners could adopt a land route created by repetitive public travel. An example is Garfield County Road 200 a/k/a North and Middle Dry Fork Canyon Roads involved in the High Lonesome Ranch litigation. Garfield County approved the long-standing route of these roads created by decades of public travel but the county did not build them.

Congress could have allowed wagon roads “by paper drawing”, as it were. The General Railroad Right-of-Way Act of 1875 (43 U.S.C. 934-939) granted a 200 ft. right-of-way across lands “in the public domain” simply by the deposit of a right-of-way map (called a “profile”) by a qualified railroad corporation which profile was approved by the Secretary of Interior. 43 U.S.C. 937 Even there, however, the railroad forfeited the granted easement if it did not build a rail bed and incept rail service within five years of depositing the profile. (Id.) Not all such railroad rights-of-way survived the five year period. In this author’s experience there were five approved railroad rights-of-way within one narrow of Colorado’s Western Slope only one of which was actually built and carried rail service.

But Congress did not adopt for wagon roads the same language and legislative scheme it adopted for railroad rights-of-way. Neither the text of R.S. 2477 nor any judicial interpretation of R.S. 2477 has countenanced the creation of an easement by decree. Actual construction or repetitive public travel (at whatever intensity level satisfies the High Lonesome Ranch decision) remain the only two grounds for such public easements.

Conclusion: Section line roads may fall into two groups: (a) those created solely by decree without any actual construction or public travel on them; and, (b) those arising independent of any county resolution. As discussed in this missive the former group were nullities ab initio. Federal law did not confer upon state or local governments any power to decree legal interests in public land.

1 This statutory authorization was repeated in Sec. 44, Colorado Statutes Annotated, Chapter 143 (1935). It was repealed in 1953.

2 “The Congress shall have Power to dispose of and make all needful Rules and Regulations respecting the Territory or other Property belonging to the United States.”

3“This Constitution, and the Laws of the United States which shall be made in Pursuance thereof ... shall be the supreme Law of the Land”. Art. VI, cl 2, U.S. Const.

James A. Beckwith

Copyright / January 2024